Love Without Gravity Introduction

In 2002, I wrote a somewhat fictionalized story about the exact moment in time when Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), the great Russian artist, realized that he could fill a canvas with lines, shapes, spaces and colors that were wholly unrelated to the way we normally see the world around us and still create a painting of great beauty and emotional impact. This remarkable event, which occurred about one hundred years ago, marked the beginning of "pure abstract art". For the first time in history, the human body, the works of man and the things of nature took a back seat in the repertoire of legitimate subjects for the artist. (Today we would say he was "thinking WAY outside the box".) I gave my story the curious title of "Love Without Gravity." Two years later (2004), when Alan Mock, the publisher of Imago magazine gave me an opportunity to write and illustrate a monthly column on art and aesthetics in his magazine, I used Love Without Gravity as the column's title. By the summer of 2005, I had written 12 more essays and stories, published each of them and, for me, completed what I had set out to do: communicate to a broad audience my views on the process and importance of making art. I then turned my attention to other things. On this page of my website you will find two stories: The first is the original "Love Without Gravity", which will remain on the website. The second story will be another of the Imago articles. At the beginning of each month, I will add a different piece from the 2004-2005 magazine series until the entire series has appeared here. This process will last until February or March of 2011. Then? If the response from you, the visitors to this website, has been positive, I may write some more. Or perhaps publish a large, glossy book containing all 13 stories together with the art that accompanied them in Imago and then use this space for something else. So, after you are done reading this page, I'd greatly appreciate if you would click on my "Contact" page and let me know what you think. Enjoy!

Winged Victory (1990)

LOVE WITHOUT GRAVITY (from the "Love Without Gravity" Series, published in Imago magazine, Issue 6, Volume 4) What does art have to do with the Laws of Gravity?

Answer: Nothing

Even now, about one hundred years since a handful of adventuresome artists began the process of discarding the traditional subjects of art (people, still lifes, landscapes, buildings, etc.) and replacing them with an endless variety of unusual and, often, unrecognizable shapes and odd color combinations, too many people still find themselves unable to appreciate much of what is called “abstract art”. And, of course, we tend to make fun of that which we do not understand. I was reminded of this just a few days ago, when one of my customers met me at Bill Jonson’s framing workshop here in Clearwater to choose frames and matts for his four new purchases. Picture by picture, we discussed colors, matts, spacing and mouldings and how each would fit with the interior design of the reception area of the customer’s clinic. One of these four pictures, “From The Wind” had been painted eight years earlier in England. I had somehow neglected to either sign or date it and there it was on the table, sold and about to be framed. I was rightly embarrassed. When it was the turn of “From The Wind” to be measured and dressed up, my two companions were suddenly silly and joking. “Which way is up?” they asked. And where was the “bottom”? Was this form a “bird”? And if we turned it the other way around, was the “bird” still a “bird”? It took us a few moments to settle down and return to the business at hand. But this interlude started me looking back over the many similar jokes and discussions that I had heard over the years. “How did I escape the Earth’s gravitic field?” I wondered to myself.

Winged Victory, (1990)

Though living on a shoestring, it was an exciting time. My studio was at one end of our rooms; Michael’s was at the other. I had been working steadily since 1968 doing what I had long dreamed of doing – creating, exhibiting and even selling art – and now I was getting a little formal training (my first and last) at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in drawing, painting and etching. It was during one of my frequent trips to the Cambridge Public Library that I happened upon a special book on modern painting. It contained a brief description of a landmark event – an event that marked the beginning (depending, of course, on which historian’s book you read) of what we now know as “abstract art”. Was the story in that book true? Or simply a good story? Although the passage of 30 plus years may have dimmed the accuracy of my recall, I will retell it here the best I can, imaginatively, with the storyteller’s personal touch. It seems that in the very early part of the last century the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky was working on a painting in his studio one bright St. Petersburg (or, perhaps, Moscow) day. He painted steadily away but as the day waned and the sun’s light grew dim (this was before electric lights) the artist, growing tired and hungry, began the ritual cleaning of his brushes. When all was tidy, he removed the incomplete canvas from the easel and hung it on a nail set in the studio wall. There it could be seen when he entered the room the next morning. He closed the door, walked to his cottage down on the next block, dined and slept the good sleep (dreaming, I imagine, of his incomplete landscape of the Russian countryside).

Being (1998) The following morning, returning to his work, he walked through the studio door, peered eagerly into the early light to where he had hung his work-in-progress and …and…to his utter surprise, a DIFFERENT painting was hanging on his wall! What magic was this? It took him only a moment to get re-oriented, but in that glorious instant he was finally able to see with crystalline clarity a work that showed NOT his landscape, NOT a scene from any aspect of life that he had ever observed, but simply a CREATION OF COLORS AND FORMS INDEPENDENT OF THE COLORS AND FORMS OF HIS EVERYDAY WORLD – and Kandinsky was free enough in mind and spirit to be struck by the beauty and wonder of it and be forever changed by that perception.

Being (1998) Stepping closer, he exclaimed, “Oh, I see!” It was now clear that in the confusion of the dimming light the evening before, he had simply hung his painting upside down. Shaking his head in amusement, he righted the canvas…but then paused, turning it upside down once again. Kandinsky gazed at it for a long while before carrying it back to the easel. The artist pulled a clean brush from a wide-mouthed ceramic jar and turned to his palette to resume work on the landscape. But his thoughts were already far away, dreaming new dreams and seeing new sights – dreams and sights created mainly by the artist himself. Vassily Kandinsky had started and once started he never looked back. He became the first great master of abstract art. Obviously, I like telling stories, but what of gravity? And what of my own art, the art of Bruce Silton in the year 2002? I am certainly not comparing myself with Kandinsky, though his influence on me is a treasured one. I have long since gone my own way, not from any compulsion to be different but through a natural evolution of knowing myself better and intending to communicate as best I can. From the titles I give to my paintings to the pictures themselves, I intend mainly to evoke (bring out) for other people their thoughts and emotions, memories of past events and anticipation of futures, their dreams and goals, their loves-and-heavens-hoped-for. I am not trying to tell you – as an illustrator might -- what to see. But I have discovered and used well, I hope, a power to draw out something of your own universe. And even something of other possible universes! And to make those universes clearer for your own pleasure or thought or experience. It should go without saying – but I better say it fast! -- that one does NOT have to paint abstractly to create such effects. (And, besides, a great many works of art are more or less abstract, combining both realistic elements and abstract elements into the making of a good picture.) Fine artists have always done what I am describing here and always will regardless of style or school. Monopolies of excellence do not exist for any one school or artist. I do believe, however, that by drawing attention off the body and off our workaday world, and onto the more abstract creation, some of the highest and best effects of art can be enhanced and even elevated. From the communications (words and looks and emotions) I receive from my audiences I know this to be true: gravity is something we all experience in these frail bodies but art is utterly individual and none experiences your universe as you do. The physicist’s sacred “Laws of Gravity” are, simply spoken, a lie -- to the artist who values his dreams.

Being (1998) Bruce Silton

Winged Victory Copyright 1990 Bruce Silton Being (3 views), Copyright 1998 ........

The Magician, 2000 ......................

(The Open Window is from the “Love Without Gravity” series in Imago magazine, Issue 4, Volume 5)

THE OPEN WINDOW

With a paintbrush, if the sky is too grey, you can split it with color and let the stars tumble to your eyes.

had been a professional painter for 26 years, when, in December of 1993, I packed my artist’s gear, locked the door of my condo overlooking Clearwater’s Intercoastal Waterway and moved 4000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean to East Grinstead, an old (1086 A.D.) English town in the rolling hills of County Sussex. My true purpose in crossing the ocean was to woo and wed Anne-Sylvie Monnier, a wonderful girl from Paris, and only secondarily (because marriage requires money) to become a textile designer.

We rented the redbrick house at 4 Morton Road, set up a studio on the third floor and got busy -- both painting and wooing.

Somehow, during the two years in England that followed (‘94 and ’95), I never married my dear “Parisienne”, though our friendship has flourished to this day. But I did learn the techniques and skills of the commercial textile designer (an artist who creates the repeating patterns that decorate the surface of woven materials.)

In the late fall of 1995, an event occurred which altered forever the way I paint and perceive art. At that time, I was working with Jeremy Talbot, a gracious London designer who had taken me under his artistic wing in a sort of unofficial “apprenticeship”. He suggested that I specialize in home furnishing designs for children and gracefully steered my talent in that direction. In November of that year, I completed a design for children that, for the first time, met my personal aesthetic standards: “The Zoo” was my best piece to date -- a hythmic tapestry of elephants, lions, fish, turtles, foxes, penguins and kangaroos painted upon a background of abstract shapes, stylized flowers and stars.

The Zoo, 1995

With the fresh artwork stowed in a battered black portfolio, I took a morning train north into London, walked from Victoria Station to Jeremy’s studio on Great Peter Street and showed him the result of my labors. Firmly (but with the great kindness that I so admired), he pointed out that while the design itself was excellent, the COLOR was probably too subtle, too complex for children -- or parent’s making purchases for their children. Could I not, perhaps, change my palette? And he then explained how I might accomplish this.

Late afternoon. The sun had vanished and the air turned cold. I sat on the return train, oblivious to the passing vista of pleasant villages and furrowed fields. Yes, I was disappointed but (more importantly) deeply intrigued by my mentor’s observations. I began to weigh the how and why of Bruce Silton’s personal palette: the treasured colors and color harmonies developed and tested since 1968. Jeremy was right, of course. Colorwise, I was still being a fine artist and it was time to put on the hat of the commercial designer.

That evening, after dinner with Anne-Sylvie, I went upstairs and began work on a “colorway” (same design, different colors) of “The Zoo”. First, I selected a 7-inch-square section of the “The Zoo”. Then, I copied its lines exactly onto another sheet of paper and simply repainted it but this time using brighter colors (straight-from-the-tube, or almost) that were likely to attract a buyer’s eye. By noon of the following day it was done.

Or, rather, almost done…for when the textile artist completes his design, he has one final task: On a narrow paper strip, he must neatly paint a sample of every separate color contained in his design. Why? Because the more colors in a design, the greater the cost to print them on fabrics -- and manufacturers consider cost before buying designs. Previously, following the customs of the trade, I had taped the color strips onto the back of the completed design. Standard procedure. But now, on a whim, I cut a paper strip to the exact length of the colorway (7”), carefully painted samples of the nine colors I had just used in the “colorway”, but tapd it not on the back but onto the front right side of the colorway and….

And a window opened, lovely and delightfully odd! By happenstance, my whimsical addition of the color strip to the design itself had, to my eyes, created a NEW work of fine art, a tiny-but-lovely painting. Inspired, I envisioned a universe of future paintings: abstract images set within borders of color that weaved into and out of the central image.

Colorway for 'The Zoo", 1995

The English winter arrived but I didn’t mind. I loved all of it. Yes, even the damp-cold that penetrates everything. At times, I could only keep warm by sitting in a steaming bathtub

I kept working. Christmas came and went. We knew we would be parting soon. I asked Anne-Sylvie to choose one of my paintings for her flat in Paris. She, of course, took my best piece. “The English Bouquet”, nicely framed, still (2005) hangs on a choice wall of her condo on Boulevard Voltaire.

The English Bouquet, 1994

hen, one day soon after the New Year of 1996, a black taxi arrived to take me to Gatewick Airport. A hug, a last kiss and we said our sad good-bye. Anne-Sylvie returned to France and I flew 7000 away to my next studio in the Los Feliz district of

Hollywood.

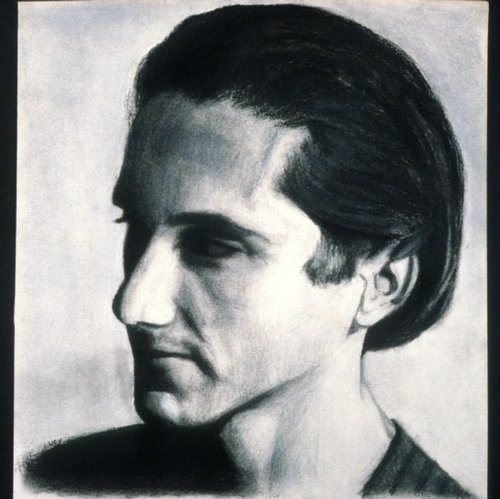

Bruce Silton, Portrait by Lucy Gott, circa 1974

|